The role of Cathar women has suffered two fates: to be demonised by their opponents and idealised by their supporters. Where does the truth actually lie?

The castle home of Esclarmonde of Foix, a prominent Cathar woman.

The historical setting

Catharism was a spiritual movement that thrived in the Languedoc region of southern France, during the Middle Ages. A wealthy semi-independent land, its nobles were often unruly and extravagant. They were cynical about the Catholic Church, which they regarded as greedy and corrupt.

What was the position of women there?

Women in Languedoc had greater legal and social equality than elsewhere in France. They could hold land in their own right if they were unmarried or widowed. There were a few ways women could earn their own living, such as in textiles, where they were admitted as masters in the cloth-making guild.

Woman Cathar ‘priesthood’ – real equality?

Some women, including from the nobility, like Esclarmonde of Foix, were initiated into the Cathar priesthood as ‘Parfaites’ and became prominent leaders. The idea of women having positions of spiritual authority was unheard of in those times, and the Catholic Church was appalled. In one public debate, a monk interrupted Esclarmonde and told her, “Go to your spinning, Madam, it is no business of yours to discuss matters such as these.” And yet, as initiated Cathars, women could preach and administer sacraments.

It’s often said that men and women were equal in Catharism. But is that strictly true? Professor Duvernay, in Cahiers d'Etudes Cathares, has traced 1,015 Cathar priests (parfaites) up to 1245, of whom about a third were women. Yet there were no women Cathar bishops and no records of deaconesses. However, women did take the initiative in setting up convents or Cathar houses for women and the matriarchs who ran them may have been deaconesses. They were at least informally powerful individuals who clearly held sway in Cathar circles, like Esclarmonde de Foix, Blanch of Laurac and Geralda of Lavaur.

The life and influence of women parfaites

Women Cathars sought to follow the life of the apostles, including healing the sick and caring for orphans, and some had medical knowledge. They led simple lives, often maintaining themselves as spinners and weavers. Many lived in single sex communities, with a same sex companion.

The network of women Cathars was also developed through family connections, both down the generations and between families through marriage and blood relations. Blanca, wife of Sicard, Lord of Laurac, for instance, became a parfait after his death. She set up a home for Cathar women and provided a regular meeting place for Cathars in the area, as well as holding public debates. In Laurac, the Cathars lived openly. Her daughter, Guirauda, married the lord of Lavaur and survived him. “She was the lady of the town” records the Catholic chronicler William of Tuleda, and “an utter heretic.”

What were the challenges from the Church facing women parfaites?

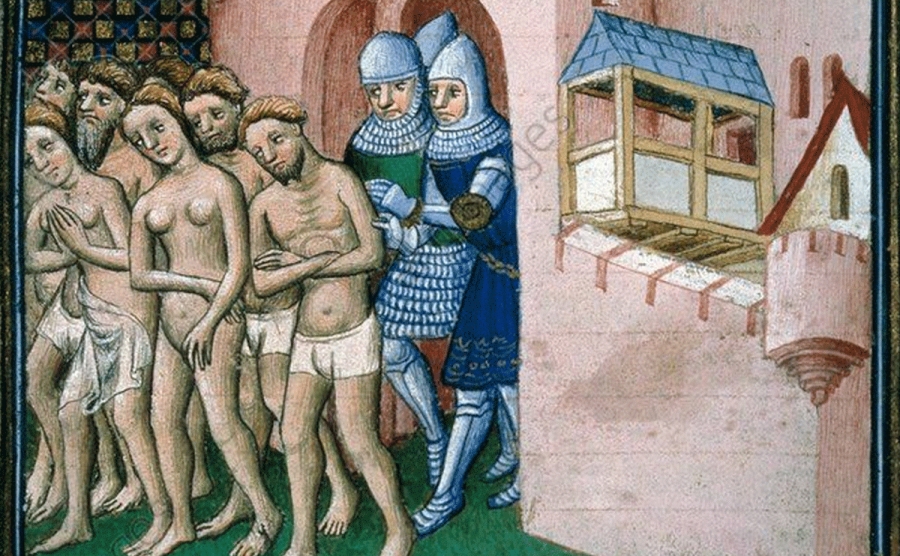

Many Cathar women, like men, faced persecution and died at the hands of the Crusade and the Inquisition. There is plenty of evidence that women stuck together in support of parfaites. On one occasion, when the Abbott of Sorèze sent an agent to arrest two parfaites, the local women attacked the individual with sticks and stones to prevent the arrest. When the Abbott remonstrated later with the women, he was told that his agent was mistakenly seeking to arrest two respectable married women.

Expulsion of the inhabitants from Carcassonne in 1209. Image from Grandes Chroniques de France.

Women in Cathar cosmology

Other than that, there is little explanation of women’s position in Cathar cosmology. In their creation story, gender is the creation of Satan – something that will be explored further in a later newsletter, The Cathars, Sex and Gender. We can only infer by their behaviour and the records of the Inquisition that women were recognised as being able to have an active spiritual role in the Cathar movement.

Perhaps the last word should be left to the Cathar women themselves, who through their actions made their feelings known. In 1218, a group of women defending the walls of Toulouse against the Catholic crusaders, hurled a large stone from a catapult and smashed the skull of its leader, Simon de Monfort, bringing his bloody and brutal life to an end.

By Thérèse Barton & Simenon Honoré

In a later newsletter, we will be exploring The Cathars, Sex and Gender.

Watch our videos on the Cathars on our YouTube channel.

Not yet signed up for our newsletter? It only takes a minute, here.

Popular posts

You might also like

Email Newsletter Our latest articles and offers delivered straight to your inbox.

Our latest articles and offers delivered straight to your inbox.